San Francisco Tour Tales

Dolly Adams, the Water Queen

Curt Gentry’s sources, in his wonderful volume The Madams of San Francisco: An Irreverent History of the City by the Bay, confused a woman named Dolly Adams – the Water Queen, with a woman named Dolly Ogden – who started up one of the Tenderloin’s early parlor houses.1 In her brief time Dolly Adams became the more famous of the two, but even though they were both active members of the demi-monde, her fame was for her performances under water rather than under the sheets.

Dolly Adams as the Swim Queen

Who was she? She was born Ellen Loretta Callahan around 1860 in New York. She was the fourth of at least 10 children, all of them girls except one boy. Her parents were from Ireland, and her father was a longshoreman who died when she was still young. Her mother had to go to work to support the family. Dolly, who was reportedly willful to begin with, grew up with little supervision and became a wayward and independent young girl. She lost her virginity when she was 16 and became a prostitute in a New York parlor house. The madam of this house introduced her to another madam, Mary Ellis, who along with San Francisco madam Diamond Carrie Maclay, persuaded Dolly to come with them to San Francisco in 1878 when she would have been about 18 years old.

Gentry said that sometime during her youth she had become a good swimmer and had developed the ability to hold her breath under water for very long periods of time. However, she herself said that she got her start at The Aquarium at Broadway and Thirty-fifth Street in New York in the late 1870s, when it first opened. The management of this venue let a group of girls learn to dive and hold their breaths underwater, undoubtedly with a view towards training a pool of inexpensive performers. Miss Adams said she was singled out by Captain Beach, another performer there, as having a special aptitude for this kind of performance, and was given:

Special lessons, so that in a very short time I was able to give an exhibition, but it was fully three years before I obtained perfect command of myself under water, for it is water into which I go, and not as many people think, an empty tank enclosed in double walls of glass, about three inches apart, the intervening space only being filled with water. Mr. Beach’s tank, in which we both exhibit, is 7 feet long, 4 high, and 2 1⁄2 wide.

This story is supported by newspaper advertisements that show a “Man Fish” performing at first alone, and then with a “Water Queen” at The Aquarium in 1880, about a year before Miss Adams gave the interview quoted above.

According to Gentry, in San Francisco she swam in the bay at North Beach and was well known for her water skills. Somewhere along the way Adams developed a risqué version of her Water Queen act, in which she appeared on stage in semi-transparent tights and dove into her glass- sided water tank to demonstrate diving and swimming techniques—as well as eating food, drinking milk, and smoking cigarettes under water—the latter feats presumably accomplished through legerdemain. Of course, the act was an excuse to see the diminutive but unusually well proportioned blonde (in some accounts she had blonde hair, in other accounts she had brown hair) swim under water and stand on stage in a wet, skin tight bathing suit.

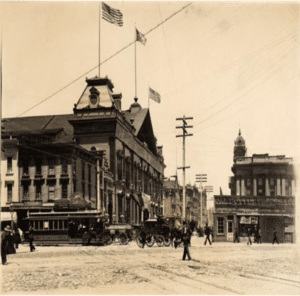

The Mechanic’s Pavilion

Adams became famous in 1879 when she attended the annual fundraiser for the Policeman’s Widows and Orphans Fund, called colloquially the Policeman’s Ball. That year’s ball was special because former President U. S. Grant had stopped in San Francisco and had agreed to attend the fête, which was held at the Mechanics’ Pavilion at Eighth and Market Streets. He was marching at the head of the solemn processional entry of the guests of honor when:

Suddenly, out of the gay throng, dashed a somewhat famous if slightly frail beauty of the period—Dolly Adams. She was attired in the conventional costume of Cupid. As well as the bow and arrow, which formed two-thirds of that attire, she carried a lily–emblem of purity. And before the General could recover from the first shock of her greeting, she had pinned the delicate blossom to the lapel of his coat.

It was said that the indomitable Grant, who had never flinched through the horror of 100 pitched battles, wilted like a wet dishclout (sic) before this unexpected onslaught.”

She won first prize for best costume.

Another part of her fame derived from:

Her laughing eye and pearly teeth, and magnificent hair of a brownish color which fell to her knees. She made many friends among the ‘bloods’ and dollars and diamonds were showered upon her.

Gentry wrote that Dolly was introduced to San Francisco sporting life during this time, and it would seem this was done either by Ellis, who had brought her out to the West, or Maclay. One of them—it’s not clear which—was probably the unnamed madam who Gentry said persuaded Adams to perform an indecent exhibition in her water tank. But the plan failed for lack of a male partner capable of performing with her under water. After performing her Water Queen act at the Bella Union and the Alhambra theaters, she returned to New York where she created a sensation at the Aquarium at Broadway and Thirty-fifth Street, and at Bunnell’s Museum at Ninth Street and Broadway. She then invested the money she had saved, of which a considerable portion was in diamond jewelry (an apparent influence of Diamond Carrie Maclay, herself a great gem collector), in operating a theatrical boarding house in New York’s Tenderloin District for two years in the early 1880s.

While she was living in San Francisco, Dolly seems to have taken her show on the road for there is a newspaper report of her performing one night in the fall of 1880 at the famous Bird Cage Saloon in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. This was during the height of the Behan–Earp feud. The Bird Cage was where everyone went at night, and the Behan/cowboy/cattle rustler/Democrat faction would sit in the boxes to the right of the stage— while the Earp/gambler/stage coach robber/Republican faction would occupy the boxes on the left. If one side cheered the act, the other side booed it, and this frequently led to gunfire. The saloon was crowded the night Dolly performed, her reputation apparently having preceded her, and the cheering and booing were consequently lustier than usual. So was the exchange of gunfire, which was said to have left twelve men dead and seven more wounded.

By the 1880s Dolly’s fame was national. For example, a woman photographer in Boston who specialized in women’s vanity portraits, kept on hand a number of photographs of female celebrities. This included “Mrs. Langtry and Bernhardt down to Maude Branscombe and Dolly Adams” so that her stage struck customers could choose the look they wanted for their own portraits. A Chicago swimming instructor cited Dolly as an example of the many actresses who are good swimmers. She was also cited as an example of women who have made their fortunes, though in Dolly’s case it was reported to be a small one, around $15,000. There were imitators, such as La Selle, The Water Queen, at the Standard Theater; and Lurline, the Water Queen, in Europe. But they weren’t necessarily copying Dolly, for there had been other Water Queens before her.

But Dolly was addicted to opium, and was living a dissipated life that eventually drove off most of her friends and forced her return to New York to see her mother, who she had been supporting. She also developed a certain notoriety. For example, Mrs. Emma Uhler, whose brother had killed a man over her in New York, committed suicide in Dolly’s lodging house, despite Dolly’s attempts to get medical attention for her. But by 1886 she had quit the boarding house business and needed medical attention herself, being desperately ill with bronchitis and pneumonia. She was cared for in her room at a cheap lodging house called the Oriental Hotel by her mother and eight sisters. The family was watching over her to make sure that no one else got Dolly’s jewelry and other valuables when she passed away. They kept her at the hotel in spite of, or perhaps because of, a doctor’s prognosis that she would die unless she was taken to a hospital. They gave up and abandoned her when she hung on, after which she was finally admitted to a local medical institution.

By July 1886 she had recovered enough to track down a friend who had absconded with a valuable bond belonging to her. The object of her search, Col. William H. Gilder, was about to leave on a five year expedition to the Arctic in an effort to be the first man to find the North Pole. At some point Miss Adams had obtained a thousand dollar railroad bond. Just before one of her trips to San Francisco, she asked Gilder to ascertain if it was worth anything and gave to him to hold for her. He never returned it and for a year and a half Dolly could not find him. She finally ran into him in Paris a year or two later, where he told her he had given the bond to one of his cousins and promised to have him send it to her in Paris. But the bond was never sent to her and that was the last she saw of Gilder until 1886, when she found him again, this time back in New York. He now claimed that the cousin who had the bond had embezzled it, along with other funds, and had fled to Canada. Dolly promptly had Gilder arrested on the eve of his departure to the Arctic, causing him to miss his ship and forcing him to get his sponsor, James Gordon Benet of the New York Herald, to make good on Dolly’s purloined bond in exchange for dropping the complaint.

She did not appear in the press again until 1888 when it was reported she had died at age 26 from the cumulative effects of syphilis, opium addiction, and pneumonia on board the steamship City of New York. She had left five weeks before to tour the Orient before sailing back to San Francisco on her way to New York because of her mother’s death. Her body was embalmed aboard ship, and she was buried in San Francisco, though the newspapers did not report where. The Public Administrator applied to administer of what was left of her estate—a little tin trunk that contained 15 five dollar gold coins, one English sovereign, $10 in Hong Kong money, a Metropolitan Elevated Railway Company of New York bond worth $1,000, six pieces of diamond jewelry, a gold watch, a chatelaine, and several fans. Oddly, he was unable to identify any heirs. Instead, the lawyer appointed to administer her estate used all of it to pay the expenses of administration, presumably including his bill.

Thus ended the story of Dolly Adams. Her legacy was thousands of publicity photographs of herself, some of which circulated in unusual ways. For example, in 1888 a man named J. G. Crawford shot and killed his wife’s ex-husband, who had been stalking and threatening her for years. At the morgue, the ex-husband’s pockets were found to be full of letters and of photographs of actresses and other well known women—including a photo of Dolly Adams.

Sources

“The Tenderloin’s First Brothels: 223 and 225 Ellis,” in The Argonaut, Vol. 22, No. 2, Winter 2011.:

The Madams of San Francisco, Curt Gentry

Other sources researched for this excerpt were the U.S. Census, the San Francisco City Directories, the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of San Francisco for 1886, 1889, and 1905, and numerous newspaper articles from the Daily Alta California, San Francisco Call, Daily Evening Call, San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco Chronicle, Sacramento Daily Record— Union, New York Daily Tribune, The Sun, Omaha Daily Bee, and the National Republican.